Representation Without Taxation

This being an election year (2007), a trend has emerged in which our politicians are falling over each other trying to figure out what new free schemes (freebies) they will give Kenyans once they become president of this country.

Whereas their anxiety to please so as to earn votes is understandable, I wish to comment on two potentially dangerous related policy initiatives being proposed, namely, more free education and now “free” taxation.

The intentions may be honorable but there are some fundamental fallacies in the manner in which they are being offered and, if taken too far, can actually lead to less and not more development.

Taxation

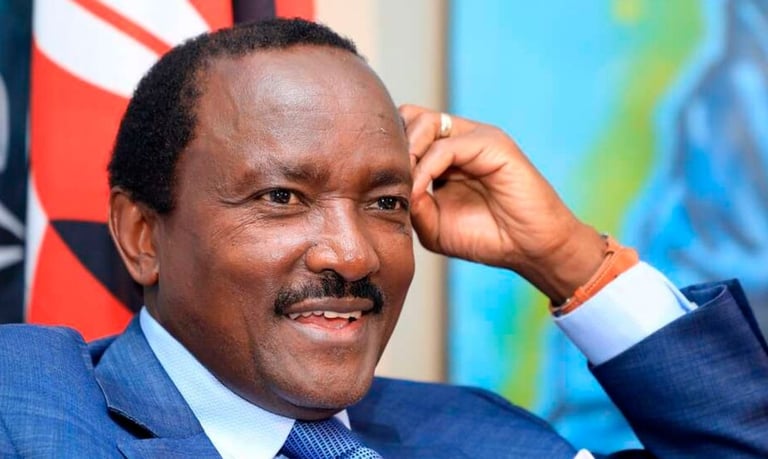

Hon. Kalonzo Muysoka has proposed that he will deliver more and more taxpayers in the low income categories out of the tax bracket. The trouble with this proposal is that it is based on the belief that lower income people are overtaxed and therefore need to be relieved of the burden of taxation. By implication, the higher income earners are under-taxed and therefore need to be hit harder. This is not entirely true.

Kenyans do not complain about high taxation in absolute terms; rather, they do so because they cannot readily see the connection between the taxes they pay and the value they get back from that tax. In the former regime, one of the greatest failures was that taxes were not being applied to give Kenyans what they expected, namely, better roads, cheaper education, better medical services, lower payments on public debt, more efficient service delivery, etc.

In effect, their argument was quite simple: Why should I continue to pay taxes when there is no connection with what I get back in return? It did not matter whether you were a rich person living in Karengata or a poor labourer walking from Kibra to the industrial area. Government was simply being told: If you cannot deliver service then you have no moral basis for asking us to pay our taxes!

The second point is more subtle and this is where Hon. Kalonzo is simply mistaken. At the end of the day democracy is about effective representation in parliament, in decision making and in allocation of public resources. Parliament and the executive can only be held accountable to the people if the people feel they have a stake in the laws being enacted and the money being spent; it is about the well-known linkage between taxation and representation.

Thus, if I am a taxpayer I have every reason to complain if I suspect that my money is being used to finance Goldenberg, Anglo Leasing and all that. Contrarily, I have no leg to stand on if I have not contributed to the money being misused or stolen since I can simply be asked:

What is your interest in all this? That is why both donors and Kenyans have been able to argue so forcibly for the prosecution of those they perceive as having stolen or misused their taxpayers’ money.

In my view, it is therefore wrong to try and remove more Kenyans from the tax bracket as a political manoeuvre. In- deed, that would be equivalent to disenfranchising them, tell- ing them they really have no mandate for electing their candidates to parliament or the presidency for that matter. By the same argument, it is also wrong for Parliamentarians to exempt themselves from paying taxes – if they haven’t contributed to the creation of that tax revenue what moral authority do they have to question how it is spent?

The bottom line is that if Kalonzo wants Kenyans’ vote, he should start by taxing himself fully, disclosing it and, in fact, including more Kenyans in the tax bracket – this can be achieved by reducing the rate of tax on lower incomes not by abolishing tax altogether. Representation without taxation is a poor democratic route – that is the curse of the oil producing and other natural resource-rich countries where it is the rulers who decide what is good for the people.

Education

Whereas education is a right to every Kenyan child not all education is a right. Economic researchers tell us that primary education is a social good because it produces a populace that is at least able to read, write and vote without having to use a thumbprint. To that extent, there is much to be said for it to be universally free – except to those who can afford it. Secondary education, on the other hand, makes it more possible for the individual to get a better job or to go for higher levels of education. Thus, it is more beneficial to the individual than to society and it is also a parental responsibility.

That being the case, there is much to be said for making secondary education not free. It is a well-known phenomenon that human beings tend to value more that which they have sweated for than that which they get for free. Therefore, a way of getting those who get secondary education to feel a sense of shared responsibility for the process is to make them pay for it. We should therefore be averse to free secondary tuition.

Indeed, in order to make education resources more equitable, I would propose more direct governmental participation in construction of education infrastructure so that the physical quality of the school is relatively uniform across the entire country and therefore the choice of the school I take my child to is less of an issue.

When it comes to university education, the equation changes completely. On the one hand, the greatest beneficiary is the individual (society will still get its share of income through taxing the individual) and therefore s/he must pay for it. The best way to deal with problem is not access per se but enablement to those who qualify and can handle it. For most university students, provision of liberal loan facilities to enable them pay for their education should be the priority – current funding is not sufficient to meet the needs of all those who can make it to university. Secondly, the choice of the institution of learning (public or private) should not be a loan condition but an individual choice since the loan is not a grant. As for the exceptionally bright and gifted, the appropriate policy should be to give them scholarships regardless of their socio-economic status or the degree programme they wish to take because of their value to the country.

Concluding Remarks

When all is said and done, the issues we are discussing boil down to one thing: economic and democratic space in that order. Given a choice, I strongly believe that most people would rather pay for a service or good instead of getting a hand-out and what we should therefore be asking is: What we can do in order to expand the opportunity matrix to both the poor and the rich so that they can participate more willingly in various social economic activities whether by way of paying taxes, educating their children or taking care of the sick and the infirm.

This will be achieved by making government concentrate on doing only those things that governments should and can do - building infrastructure, providing key social services, protecting civil liberties and, in general, creating an enabling environment in which all can make their own consumption and investment choices and having effective mechanisms for holding the government accountable.