The SGR is Here, Finally

Exactly a year ago, I had the privilege of experiencing first-hand the ongoing construction of the Single Gauge Railway(SGR).

This arose out of a request I had made to the CEO of Kenya Railways, Atanas Maina, that as a member of a senior government commission(CRA), I had some undefined right to know what the central government had been doing with the money we had asked Parliament to allocate to it.

As it turned out, my request was well received both by the government and my Commission. We were, accordingly, given permission to go and see what was happening on this project which was perceived by many people as being “top secret”.

And that is how four commissioners and several senior members of staff set out on what was to become one of the best site tours I had been for the last five years.

The Start of the Tour

The tour started at Syokimau Station where the new station terminal building was still under construction. At this point, there was no evidence of the SGR as it was still crawling up from beyond Athi River. This made me suspect that there was more hype than reality on this railway.

Mr. Maina, the MD, finally arrived to give us a briefing not only of our tour but several other pertinent details. One of these details was a graphic model layout showing the route from Mombasa all the way to Nairobi.

I took a photo just to be on the safe side. After the introduc- tion, he handed us to two engineers who were going to be our guides on this safari – one Chinese, one Kenyan.

“Why two engineers?”, I asked him.

“Because”, he chided me, “this is a joint project and we want you to get both sides of the story. The Chinese can speak English and the Kenyan can speak Chinese so you won't get conflicting information. This is how we have been doing this project”.

As we left Syokimau armed with several brochures, I started feeling like one of those British explorers who did the original railway line between 1895 and 1901. Only I was doing it in reverse. More than a hundred years later.

Athi River Crossing

Very soon thereafter, we were on our way to Athi River via the lower part of the Nairobi National Park and were instantly awed by the massive concrete pillars making their silent way through the Park.

“How do they get those massive structures here?”, I asked. “Just you wait”, says he. “You ain’t seen anything yet”.

After the Athi River crossing, that is when I realized that I was witnessing a modern day engineering miracle of unimaginable proportions...

As we headed towards Machakos turn-off then on to Emali and on to Mtito Andei, I confirmed my worst fears – that his- tory was being made right here and no one was paying much attention. Especially our politicians many of whom had no clue what this massive project was all about.

Railway Current Cost Equivalent

COST COMPARISONS

While the cost of the original railway was £5.3 million in 1900, we can estimate its current equivalent by applying three factors: One, the “pure” time value of money adjustment over the last 116 years (2.5%); two, the average rate of inflation of the British pound in the period (3%) and the exchange rate for the pound over that period.

Adjusting of these three factors alone suggests a current cost of £2.64 billion. At the current exchange rate of around KShs 140 to the £, this amounts to Kshs. 369 billion. This would be the amount it would cost to replace the existing railway line using the same route and mate- rials, an unlikely proposition.

Given that the SGR is vastly superior in all aspects, the minimum cost would be 2 to 3 times that cost, i.e., be- tween KShs. 740 billion and KShs 1,110 billion.

You can use those kinds of numbers to compare with the actual cost of the 500 km Mombasa–Nairobi section KShs 327 billion. But be warned: These kinds of comparisons are relatively useless.

A Bit of History

Way back in early 1890s, the directors of the Imperial British East Africa (IBEA) company realized that penetrating the arid and hostile Kenya landscape to get to Uganda was going to require a vastly different approach from the caravans they were then using. That was when a brave engineer came up with a solution: A railway line that would wind its way all the way to Lake Victoria (appropriately named after the British queen) and then on to the source of the Nile at Jinja in Uganda.

This would allow Her Majesty’s government to have total control of the source of the Nile in the event those crazy Egyptians started having ideas about using the 200 km Suez Canal to frustrate British efforts to go to India and the Far East. Recall that the Canal that shortened the journey to those distant lands by 7,000 kilometres was opened in 1869 and was a game- changer as far as British trade was concerned. Controlling the source of the Nile was therefore of strategic importance to Britain – in retrospect, a far-fetched ambition.

The railway line was estimated to cost about £7.5 million but the government agreed on giving the company only £5.3 million to do the job. As it turned out, this was the money that was actually used to pay for the rail stock, machinery and the engineers (all British) the rest being procured through cheap Indian and local native labour. If you factor in the hardships endured and the lives lost to both man-eaters of Tsavo and diseases (more than 24,000 people, mostly Africans, died over the 5- year construction period), the cost changes considerably. And, of course, there was no compensation for the land acquired along the way.

Back to the SGR

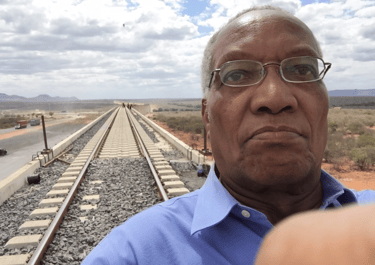

From Emali and Mtito Andei, we ended up at the Tsavo River crossing. This is perhaps the most remarkable section of the railway line as it flies many metres over the river on its way to Nairobi. I can safely predict that this will be one of the most picturesque parts of the railway line and a film maker's dream. It makes those pedestrian engineers of the old rail look like Neanderthals. I took a selfie which I hold dear among my travel memorabilia.

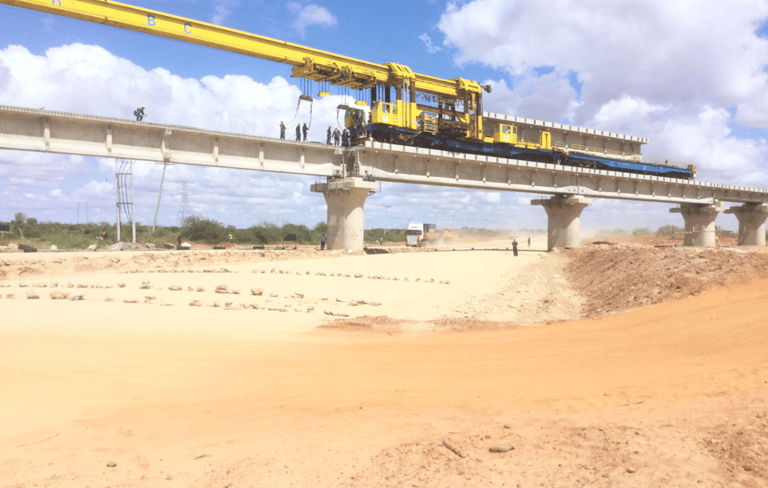

Our final stop was to witness the completion of the Taru overpass. If you have never been to Taru, this is the place where they had to do an overpass over the Mombasa-Nairobi highway without interfering with the traffic flow. It is the place where the Chinese show-cased their superior rail construction technology as they moved the massive sectional rail pre- fabs to be laid gently on concrete pillars, aligned them and then soldered all together. It is the one time that I wished I had become an engineer instead of a mere bean counter!

Value Propositions

Along the way, we kept asking questions about all sorts of things and this is where I summarise the most important ones:

1.The fabrication of all the concrete materials was done in a huge warehouse located at Mtito Andei – the pillars, the rail sleepers, the drainage system using special local cement;

2.While the main rail track was specially imported from China, the fabrication was all done here in Kenya;

3.The Chinese engineers were required to have a Kenyan understudy and to ensure that there was genuine knowledge transfer;

4.Wherever there were questions about whether to use Chinese or Kenyan technicians, the preference was always in favour of the Kenyan;

5.There was express design component that required there would be specific value addition to the communities through whose areas the

rail passed in order to avoid the mistakes of the original rail which was meant to be exclusively for the benefit of the colonialists;

6.Environmental considerations were given high priority given the terrain through which the rail passed as well as certain aesthetic nuances.

In short, pretty little was left to chance but you would have to use the new rail to appreciate many of them.

Final Word

A project of this magnitude will have its critics and its proponents as expected. The benefits of having this new rail cannot, in my view, be overemphasized. As a financial consultant, I can say this: Conventional cost/benefit analysis by some of our economists suggests that the costs outweigh the benefits.

I beg to differ. The tools of analysis used by the old school cost-benefit analysts including those at the World Bank tend to underestimate the benefits simply because they do not know how to measure them. Or worse, they do not wish to recognise them.

However, there is new intellectual knowledge that suggests that the value proposition for some projects may be much higher than could be imagined in the confines of a bureaucrat’s office or an academic lab. Two local examples will suffice: One, the building of the Thika Super Highway has resulted in massive developments on both sides of the highway stretching all the way to Sagana. All you have to do is an aerial Google earth map to see what is happening.

Two, a curious paragraph in the 2016 Annual Report of Safaricom Ltd says that, after using modern methods of Cost/Benefit analysis, the true value of their product Mpesa to the country has been estimated to be at least 10 times the profit of Sh 38 billion that the company made in 2016, i.e., Sh 380 billion. That should be a wake-up call to other organisations that never seem to think about such issues.

Otherwise, why would the good old Queen Victoria have agreed to spend a fortune to give savage African natives an opportunity to see beyond their dark continent? My admonition to the politicians along the route of the railway line is to maintain a long-term view that seeks answers to what they can do to make money out of the new railway line or improve the quality of life for their residents.

Instead of just asking for "fair" compensation for "my people" and other forms of extortion that Kenyans are notorious for.

Prof JH Kimura

Nairobi,

30th May 2017.

Tsavo River Crossing

Taru Overpass Crossing

Artists’ impression of Mombasa- Syokimau line