The Sorcerer’s Return

One of the best known Kenya’s colonial writers is a lady known as Elspeth Huxley(1907-1997). She came to Kenya in early 20th century as a little girl to join her mother who was was trying to establish a farm around Thika.

That was a long time ago and the book she wrote then, “The Flame Trees of Thika” (1959) is one of the best books I have read about colonial Kenya. Partly because she was writing about an area I was to become quite familiar with and about a town where I started my first full time job.

This was way back in 1966 after I finished my A-levels in a school in Embu known as Kangaru School. I must say it was an unfamiliar school and my reason for going there in the first place was was to avoid going to other schools I had no respect for.

As it turned out, the school was quite good and advanced but I had one small problem: We were required to select three subjects for our A-levels and a fourth one, General Paper, which was compulsory. The three subjects were further divided into two clusters: Arts and Science according to a Cambridge University determined order.

My small problem was in the choice of my three subjects. I therefore selected, in order of preference: Mathematics, Physics and English(Literature). And that was where my little problem started. As you can imagine, that was an untenable combination. To cut a long story short, the problem was resolved by allowing me to take Maths and English but drop Physics and replace it with Geography. A timetabling change was made to accommodate this cranky fellow from the hills of Murang’a.

On to University

On completion of my A-levels, I had to choose what to do at university. And that is how I ended up getting into the Bachelor of Commerce degree specialising in Accounting a subject I knew absolutely nothing about.

As the New England poet Robert Frost once wrote, having come to a junction on a yellow road, I had to choose one since I could not walk both paths hoping that, some day, I could get back “on the road not taken”. Easier said than done as I subsequently found out.

The rest, like they say, is history. I went on to graduate as a BCom student, then MBA in a distant place called Edmonton, Canada before making the final jump across the border for a PhD at UCLA specialising in accounting and finance. Which enabled me to spend the early part of my life as an academician.

Enter the Sorcerer

It was while I was doing my PhD that I met a Kenyan-born professor, John W Buckley, with whom I developed a good relationship especially because he had risen to become the Dean of the business school at UCLA. He was, strangely, teaching a course on research methods for business students.

It was in this course that he introduced us into the intricate science of field research and specifically data gathering. He made us read a strange book called “Journey Into Ixtlan” by Carlos Castanada a former student, I think, at UCLA. The research Castanada was conducting involved finding out from the Red Indians of Southern California and New Mexico how they were able to survive in such a harsh climate.

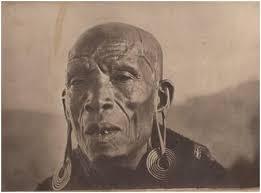

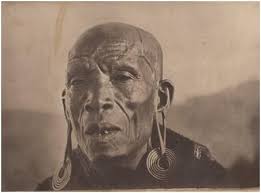

As can be imagined, it was not easy. He had to find a mzee who was well informed about the culture of the Indians. In short, a sorcerer who would be willing to allow him to observe how he was going about his arcane business. Without asking questions because that was how sorcerers worked.

The long and short of it was that he was able to learn a great deal, finish his PhD thesis and to have it published in book form. He decided to specialise in that area and is now a world scholar and well published on the so-called primitive people’s cultures.

Return of the Sorcerer

There is a saying that once hooked onto something that you enjoy, you will always go back to it. And that is how this sorcerer ended up re-discovering his favourite subject: sorcery in its modern permutations. This includes such arcane arts as predicting corporate bankruptcy using accounting data, identifying corporate thugs using psychometric instruments and other related aspects of corporate behaviour.

Which, as you can imagine, takes us back to Elspeth Huxley. I recently returned to reading one of her classics, a book by the title “Red Strangers” which describes in excruciating detail the life of the Kikuyu people of Nyeri(Gaki) before and after the coming of the colonisers. It is not the kind of book you can risk reading unless you are “Gikuyu damu” and have nerves of steel.

Because, sadly, the successive social disasters currently facing the people of Central Kenya are all clearly visible from her descriptions. The book was, in fact, banned by the the British government soon after it was published in 1938.

The main reason for the ban: It painted the Gikuyu tribe in a favourable light an image that the colonisers did not want told.

The rest, like they say, is history.

JH Kimura, PhD

Nairobi,

July 2019

In retrospect, I should have completed reading this book earlier because the ending is far more promising than I could have ever expected. Especially that last bit when the son of the second protagonist Karanja takes a bet on getting a ride in a mzungu’s plane. This was after he returned to Njoro after burying his father Matu in Nyeri. He won the bet and flew in te plane!

I say so because without the book I would never have been able to assist Mrs Winnifred Waibochi complete writing her own version of the “red strangers” entitled “This Place Nyeri” which is about to get published. Mrs Waibochi is my daughter’s mother-in-love and the grandmother of my first three lovely grandchildren Teshi Wambui, Naledi Ngima and Baraka Waibochi.

Gives assurance to the fact you can never tell where the road you have taken will lead you.